This month’s blog from our Community Geologist, Dr Ian Kille, is all about …fish and bones!

If you’d like to receive our monthly newsletter and get involved with our Stone Sourcing activities, sign up as a volunteer here.

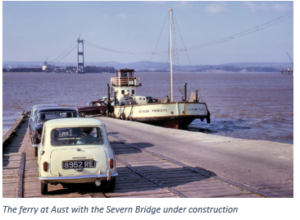

The first time I went to Wales we took a ferry from Aust on the east and English bank of the Severn to Beachly on the west and Welsh side. The next time I went to Wales we drove across the Severn Bridge with barely a glance at Aust a way down below us. I wish I had known then that the nearby cliffs at Aust form a famous exposure of the Rhaetic bone bed – I would definitely have been on the case with Mum and Dad. It wasn’t until several years later, in my teens, through exploring beds of the same age at Blue Anchor (not far from Minehead in Somerset and the home of my grandparents) and a trip to Aust with my old pal and co-geology nerd Kevin that I go to know and see what it was about. Till that point fossils had been about invertebrates – devil’s toenails (gryphaea), crinoids, corals, ammonites and trilobites. Vertebrates were a whole new layer of excitement and in these bone beds there was plenty to get excited about. Fish scales and ichthyosaur teeth and occasionally a piece of plesiosaur vertebra. These fossils have a different look and feel to them, preserved in phosphate minerals rather than carbonates and oxides and they had dark shiny surfaces, particularly the fish scales. Beneath their surface the bones had a distinctive spotty texture revealing a vascular structure where the blood vessels feeding bone growth would have been.

The first time I went to Wales we took a ferry from Aust on the east and English bank of the Severn to Beachly on the west and Welsh side. The next time I went to Wales we drove across the Severn Bridge with barely a glance at Aust a way down below us. I wish I had known then that the nearby cliffs at Aust form a famous exposure of the Rhaetic bone bed – I would definitely have been on the case with Mum and Dad. It wasn’t until several years later, in my teens, through exploring beds of the same age at Blue Anchor (not far from Minehead in Somerset and the home of my grandparents) and a trip to Aust with my old pal and co-geology nerd Kevin that I go to know and see what it was about. Till that point fossils had been about invertebrates – devil’s toenails (gryphaea), crinoids, corals, ammonites and trilobites. Vertebrates were a whole new layer of excitement and in these bone beds there was plenty to get excited about. Fish scales and ichthyosaur teeth and occasionally a piece of plesiosaur vertebra. These fossils have a different look and feel to them, preserved in phosphate minerals rather than carbonates and oxides and they had dark shiny surfaces, particularly the fish scales. Beneath their surface the bones had a distinctive spotty texture revealing a vascular structure where the blood vessels feeding bone growth would have been.

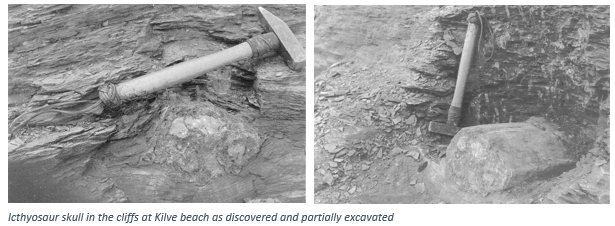

Another few years later whilst on a holiday in Minehead as an older teenager, I borrowed my Nan’s Moulton style bike, with its tiny fat wheels. I headed off for several days exploring the coast, blissfully in control of my own plans, staying in the youth hostel at Quantoxhead. On the last day of my planned trip whilst nosing around in the layered limestone-and-shale cliffs at Kilve Beach, I spotted a ring of material about 6 inches across which had this spotty, vascular texture in it. It was a large piece of bone and in a shape that suggested the snout of a skull. I spent the whole of the rest of the day excavating chasing the bone back into the cliff. The more I dug the larger it got!  Late in the afternoon I realized I wasn’t going to get back to Minehead at the agreed time, so found a phone box and called to let my folks know that I was ok, but that I had found a dinosaur and needed a bit more time and a lift. It was later identified as likely belonging to an Ichthyosaur. This chunk of skull is now somewhere in the Oxford Museum of Science, still awaiting preparation even after 40 years in residence. Having recently indulged myself by purchasing an air scribe (the fossil preparation tool of choice) I am now considering the possibility of repatriating the skull to do the work on it myself.

Late in the afternoon I realized I wasn’t going to get back to Minehead at the agreed time, so found a phone box and called to let my folks know that I was ok, but that I had found a dinosaur and needed a bit more time and a lift. It was later identified as likely belonging to an Ichthyosaur. This chunk of skull is now somewhere in the Oxford Museum of Science, still awaiting preparation even after 40 years in residence. Having recently indulged myself by purchasing an air scribe (the fossil preparation tool of choice) I am now considering the possibility of repatriating the skull to do the work on it myself.

This fossil was from the Lias, the oldest formation of the Jurassic period and at about 200 million years old is approximately 100-140 million years younger than the fossils to be found in the Carboniferous of the Northumberland Coast and the central and eastern part of Hadrian’s Wall. In the Carboniferous Period ammonites and dinosaurs, for which the Jurassic is famed, were in the distant future. The ammonites’ ancestors were there in the shape of goniates. These were spiraled like ammonites, but with much simpler suture lines marking out the division between their floatation chambers as has been explored in my earlier blog “Suckered”. As for the vertebrates, the Carboniferous precursors of the dinosaurs had made it onto land in the shape of the very first amphibians: this is another story for another blog entry. The other vertebrates that were there were the fishes.

This fossil was from the Lias, the oldest formation of the Jurassic period and at about 200 million years old is approximately 100-140 million years younger than the fossils to be found in the Carboniferous of the Northumberland Coast and the central and eastern part of Hadrian’s Wall. In the Carboniferous Period ammonites and dinosaurs, for which the Jurassic is famed, were in the distant future. The ammonites’ ancestors were there in the shape of goniates. These were spiraled like ammonites, but with much simpler suture lines marking out the division between their floatation chambers as has been explored in my earlier blog “Suckered”. As for the vertebrates, the Carboniferous precursors of the dinosaurs had made it onto land in the shape of the very first amphibians: this is another story for another blog entry. The other vertebrates that were there were the fishes.

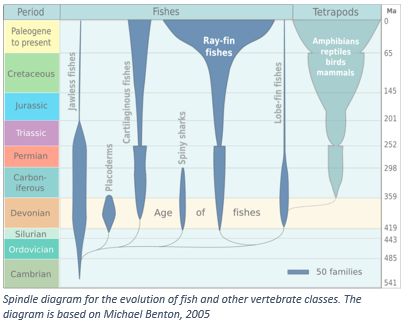

When I started writing this blog, I had intended to map out the evolution of fish. However, it became clear that this would involve writing a book; so here is a quick leap through some of the highlights.

Hag fishes are strange creatures with loose skin and an ability to produce prodigious amounts of slime which combine to make them very difficult to eat. The hagfish and the parasitic lampreys belong to the same class of fish, the Agnatha or jawless fish,

Hag fishes are strange creatures with loose skin and an ability to produce prodigious amounts of slime which combine to make them very difficult to eat. The hagfish and the parasitic lampreys belong to the same class of fish, the Agnatha or jawless fish, which were the first to evolve. The jawless fish arrived early in the evolutionary history of multicellular creatures, appearing at the outset of the Cambrian Period at about 530 million years ago. These were simpler creatures than their distant modern relatives, probably filter feeders and with a notochord (like that found in an embryo) a rod like precursor to the development of vertebrae.

which were the first to evolve. The jawless fish arrived early in the evolutionary history of multicellular creatures, appearing at the outset of the Cambrian Period at about 530 million years ago. These were simpler creatures than their distant modern relatives, probably filter feeders and with a notochord (like that found in an embryo) a rod like precursor to the development of vertebrae.

Fish with true vertebrae evolved later in the Cambrian period. Still part of the jawless fish family, they included armoured fish, (Ostracoderms) and Conodonts. The latter are small eel-like creatures previously know only for their teeth-like structures and highly valued as zone-fossils. It is from the Ostracoderms that an evolutionary line can be traced to the first jawed fishes (the epic Placoderms) and then to the explosion of fish types that marked the end of the Silurian and the beginning of the Devonian Period.

These new fish groups included the now extinct spiny sharks (Aconthodii), the cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes) which includes sharks and rays, and the bony fishes (Osteichthyes). The bony fish further evolved at this time into the ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) and the lobe-finned fishes (Sarcopterygii). We are familiar with the lobe finned fishes in the shape of Coelacanths which were thought to have become extinct in the Cretaceous but in 1938 were discovered living in the Indian Ocean. It is from the lobe-finned fishes that the first tetrapods, the early amphibians, evolved. The ray-finned fishes are even more familiar in the shape of haddock, mackerel, piranhas and goldfish amongst many others.

These new fish groups included the now extinct spiny sharks (Aconthodii), the cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes) which includes sharks and rays, and the bony fishes (Osteichthyes). The bony fish further evolved at this time into the ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii) and the lobe-finned fishes (Sarcopterygii). We are familiar with the lobe finned fishes in the shape of Coelacanths which were thought to have become extinct in the Cretaceous but in 1938 were discovered living in the Indian Ocean. It is from the lobe-finned fishes that the first tetrapods, the early amphibians, evolved. The ray-finned fishes are even more familiar in the shape of haddock, mackerel, piranhas and goldfish amongst many others.

Having leapt through the evolution of fish, let’s go back to the beautiful foreshore at Cocklawburn Beach just south of Berwick-upon-Tweed, where rocks of the mid-Carboniferous Period are exposed. Not long after I first moved to this part of the world, I was exploring the limestone skerrs at Cocklawburn and was surprised to come across the very same shiny phosphatic bony material with the spotty vascular interior that I had noticed so many years ago at Kilve Beach. This is mystery rock number 18 for the Hadrian’s Wall Community Archaeology Project. It had something of the shape of a shoulder blade about it but about 12 inches across. I also noticed that nearby there were several square cuts in the rock where small slabs of rock had been removed with a saw. Enquiry revealed that a (then) teenager, Max (who happened to be the son of Mick Manning and Britta Granstrom, then our neighbours and well known as a children’’ author, and illustrator and artist respectively) had made a discovery. The piece of bone was the last piece of this discovery, unnoticed or left behind for some reason, the rest having been collected by the Hancock Museum with permission from the Northumberland Coast AONB partnership. The find has been identified as the remains of a Rhizodont fish, a now extinct member of the lobe-finned class of fish. The remaining bone gives a clue to the size of this creature. As part of what would evolve into a shoulder this implies that this fish was many metres long. The Rhizodonts were predatory fish with vicious teeth so this would not have been a good fish to be swimming with.

Having leapt through the evolution of fish, let’s go back to the beautiful foreshore at Cocklawburn Beach just south of Berwick-upon-Tweed, where rocks of the mid-Carboniferous Period are exposed. Not long after I first moved to this part of the world, I was exploring the limestone skerrs at Cocklawburn and was surprised to come across the very same shiny phosphatic bony material with the spotty vascular interior that I had noticed so many years ago at Kilve Beach. This is mystery rock number 18 for the Hadrian’s Wall Community Archaeology Project. It had something of the shape of a shoulder blade about it but about 12 inches across. I also noticed that nearby there were several square cuts in the rock where small slabs of rock had been removed with a saw. Enquiry revealed that a (then) teenager, Max (who happened to be the son of Mick Manning and Britta Granstrom, then our neighbours and well known as a children’’ author, and illustrator and artist respectively) had made a discovery. The piece of bone was the last piece of this discovery, unnoticed or left behind for some reason, the rest having been collected by the Hancock Museum with permission from the Northumberland Coast AONB partnership. The find has been identified as the remains of a Rhizodont fish, a now extinct member of the lobe-finned class of fish. The remaining bone gives a clue to the size of this creature. As part of what would evolve into a shoulder this implies that this fish was many metres long. The Rhizodonts were predatory fish with vicious teeth so this would not have been a good fish to be swimming with.

The surge of excitement when I found the Icthyosaur skull remains vivid in my mind and finding the bone at Cocklawburn reminded me of that time. I imagine Max may have experienced that excitement too and I know many geologists who retain this feeling, and whilst some of them are paid-up professional geologists many of them are amateurs. The world of geological discovery is there for all, and for the young this maybe the beginning of a lifelong fascination.

The surge of excitement when I found the Icthyosaur skull remains vivid in my mind and finding the bone at Cocklawburn reminded me of that time. I imagine Max may have experienced that excitement too and I know many geologists who retain this feeling, and whilst some of them are paid-up professional geologists many of them are amateurs. The world of geological discovery is there for all, and for the young this maybe the beginning of a lifelong fascination.

Attributions

Aust Ferry: By Adrian Pingstone – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4095255

Goniatite: CeCILL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64362

Fish evolution diagram: By Epipelagic – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24336974

Hagfish from: https://phys.org/news/2011-03-hagfish-skin.html

Lamprey mouth from:https://www.washington.edu/news/2009/07/23/ancient-sea-lamprey-dramatically-transforms-its-genome/